Many thanks to Rebecca Fraser, manager of a

community organisation that works with single parents, for this post.

The Budget released this week described

an almost immediate end to the Kiwisaver $1000 kick-start incentive. We know that inequality is growing within our current system and unless

we start to look at things very differently, it will continue to grow. However, even within the system, sometimes

there are mechanisms that work against unfairness. The Kiwisaver $1000 kick-start incentive was

one of these. Income based retirement

schemes like Kiwisaver tend to perpetuate inequality, because they

don’t level out the playing field for people. The disappearance of the

kick-start incentive makes the system worse.

Who

is disadvantaged by the disappearance of the $1000 kick-start? They

don't collect ethnicity stats about Kiwisaver take-up so we don't have any data

about which ethnicities are enjoying the extra $1000. My reflection of this is

based purely on what people I know have told me, when I asked them. Almost

always I have heard from working Pākehā that they are enrolled in Kiwisaver and from

working Māori that they are not, and I have

noticed this trend amongst people I have employed. It might be different in

different workplaces and sectors - I hope.

Because

why would you save for a retirement when you're more likely to die before you

get there? Māori are expected to live 7.3 years less than non-Māori. The gap is reducing, but not quickly. Having

money in one's retirement inevitably prolongs life where lack of money shortens

it but due to lifetime employment and income patterns, women are more likely to live in poverty

in retirement than men, and Māori more than

European. People who might not make it to retirement are not naturally

incentivised to join a retirement savings scheme.

People

who do not expect to own their own home are not naturally incentivised to join

a scheme that can help them with the deposit on their first home. With Māori home ownership rates at 28.2% vs.

European at 56.8%, people’s expectations that Kiwisaver would prove useful

might understandably be different.

And

people who are struggling to make ends meet right now are not naturally

incentivised to join a retirement savings scheme. Fair enough too, a bun in the

hand is worth more than a loaf in the trees, as it were. According to the

indicators about inequality for Māori

and Pacific people put forward by the Victoria Business School,

Māori end up with $96 a week less than

European, on average. And this is only

one small measurement of the current inequalities of our system.

All the little inequalities add up. The tricky little fact that children who are

not earning any money could sign up to Kiwisaver and gain the $1000 incentive was,

in my experience, a piece of information shared across monied connections. A

mortgage consultant looked at my daughter when I brought her into the bank and

handed me a sheaf of forms that required signatures and proof of ID from both

parents to sign her up for Kiwisaver. But people who don't have regular discussions

with bank managers, people whose negotiation with the other parent of their

child can barely cope with whose turn it is to drop them at school, let alone

which Kiwisaver scheme to opt the kid into, people whose daily existence is in

the 'Let’s get through it' mode rather than 'Let’s think about what happens when

you're 70' mode - these people could all have done with the $1000 kick-start

that isn’t available any more.

People

who might not have natural incentives to join a retirement savings scheme is anyone

for whom life is not an orderly procession from school to university to a job

to marriage... home ownership, a couple of kids, a regular holiday in Fiji, the

eventual divorce, the delighted remarriage, honeymoon in Europe and a peaceful

retirement.

People who, in other words, distrust that the system will work for

them, with good reason.

And

they *are* perfectly good reasons not to take up Kiwisaver. But 'perfectly good

reasons why not' are EXACTLY why incentives need to be in place. Incentives

like the $1000 kick-start. I am gutted for us. I watched John Key on TV last night dismiss concerns

by saying something to the effect of 'Well,

it has been around for ages and they've had the chance, so if they haven't done

it by now then they were never going to.' He is wrong. Incentives are not in place for the people

who can get over the finish line first, but to encourage the people who feel

like they’re not even in the race to begin with.

I bet his retirement still feels pretty cosy.

Star Wars was my first movie, a metaphor for tolerance if not

celebration of difference if ever there was one. I’ve explored ideas

about social structures through science fiction ever since.

So when Torchwood began it was a no-brainer I’d be watching.

Aliens.

Gadgetry. Explicit and regular examination of gender and power.

Probably the hottest sex scenes, with all manner of couplings, I’ve seen

on a mainstream television show, because desire is explicit by everyone

participating. Set in Wales, so able to gently critique England as the

centre of the universe, and using that as a plot mechanism, repeatedly,

to explore issues of class. Every single main character exploring

attraction at one point or another to the same and different genders.

Aliens.

Gadgetry. Explicit and regular examination of gender and power.

Probably the hottest sex scenes, with all manner of couplings, I’ve seen

on a mainstream television show, because desire is explicit by everyone

participating. Set in Wales, so able to gently critique England as the

centre of the universe, and using that as a plot mechanism, repeatedly,

to explore issues of class. Every single main character exploring

attraction at one point or another to the same and different genders.

Season 3 is remarkable. Brutally stripped back plot spoiler: Aliens want to take 10% of Earth’s children as recreational drugs. They will release fatal viruses if Earth’s leaders don’t agree. They can do this; they have the technology.

What makes it remarkable is for the first time, Torchwood turns their beam on the machinations of the state responding to the crisis, in particular, the British government. A kinda sci-fi imagining of how western governments might react to such a dilemma.

We don’t come out well. The UK government had authorised, in 1965, a gift of 12 children to the same aliens, from a children’s home because “no one will miss them.”

The theme is extended to present day. First British ministers offer asylum seeking children in detention centres. When this isn’t enough for the aliens, the British state decides they cannot risk the children who will work in our hospitals and our schools, run our country. But the Deputy Prime Minister says some children matter less:

The British Ministers don’t like what they are doing. There is no joy. But there is the ability to decide that some people are worth less than others. That some people matter less. And therefore, the ability to sanction the unspeakable.

This series was almost unwatchable. As with all good sci-fi, the issues it was exploring were only human. How do we decide worth? What is the power of the state for? When it comes down to it, where do you stand?

One of the many scenes which made me cry featured unarmed men on one council estate running at soldiers kitted out with batons, guns and riot gear, to try and buy their children time to run away. And one police officer, watching in horror, taking off his uniform to fight with the men he knew, rather than stay safe with the state.

Fantastical? Not so much. Can we really say, in Aotearoa today, that all of our children matter the same to the state?

The most obvious parallel is New Zealand armed police rolling into Tuhoe, treating the children of Ruatoki with absolute disdain. Police boarding schools buses, terrifying kids, detaining them illegally. It’s hard to imagine similar actions being signed off for buses headed to private schools in predominantly Pakeha areas.

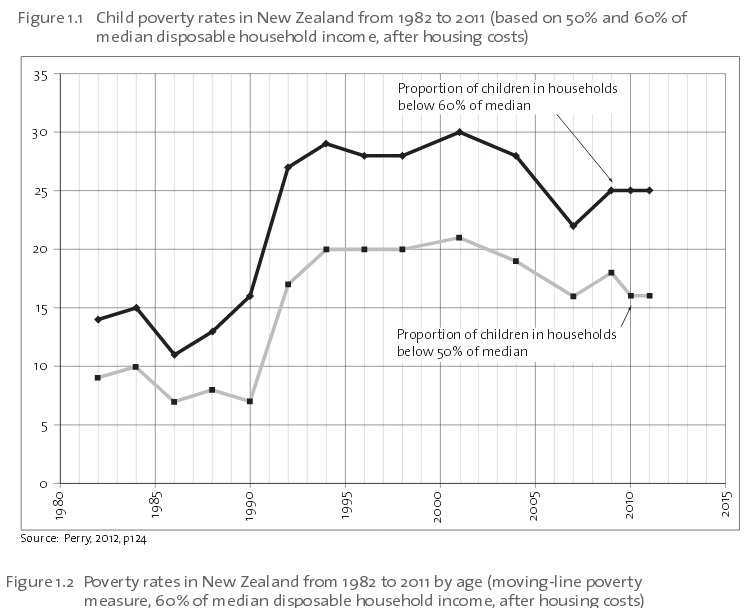

But there are other parallels too, where the state might not be clad in riot gear. About 270,000 New Zealand children live in poverty, according to the Children’s Commissioner. These levels go up and down, depending on the state’s actions:

So when Torchwood began it was a no-brainer I’d be watching.

Aliens.

Gadgetry. Explicit and regular examination of gender and power.

Probably the hottest sex scenes, with all manner of couplings, I’ve seen

on a mainstream television show, because desire is explicit by everyone

participating. Set in Wales, so able to gently critique England as the

centre of the universe, and using that as a plot mechanism, repeatedly,

to explore issues of class. Every single main character exploring

attraction at one point or another to the same and different genders.

Aliens.

Gadgetry. Explicit and regular examination of gender and power.

Probably the hottest sex scenes, with all manner of couplings, I’ve seen

on a mainstream television show, because desire is explicit by everyone

participating. Set in Wales, so able to gently critique England as the

centre of the universe, and using that as a plot mechanism, repeatedly,

to explore issues of class. Every single main character exploring

attraction at one point or another to the same and different genders.Season 3 is remarkable. Brutally stripped back plot spoiler: Aliens want to take 10% of Earth’s children as recreational drugs. They will release fatal viruses if Earth’s leaders don’t agree. They can do this; they have the technology.

What makes it remarkable is for the first time, Torchwood turns their beam on the machinations of the state responding to the crisis, in particular, the British government. A kinda sci-fi imagining of how western governments might react to such a dilemma.

We don’t come out well. The UK government had authorised, in 1965, a gift of 12 children to the same aliens, from a children’s home because “no one will miss them.”

The theme is extended to present day. First British ministers offer asylum seeking children in detention centres. When this isn’t enough for the aliens, the British state decides they cannot risk the children who will work in our hospitals and our schools, run our country. But the Deputy Prime Minister says some children matter less:

“If we can’t identify the lowest achieving 10% of this country’s children, then what are the school league tables for?”So the army rounds up children at school. Many, many parents keep their children home. The army rolls into working class areas, into council estates, and pulls children away from screaming parents.

The British Ministers don’t like what they are doing. There is no joy. But there is the ability to decide that some people are worth less than others. That some people matter less. And therefore, the ability to sanction the unspeakable.

This series was almost unwatchable. As with all good sci-fi, the issues it was exploring were only human. How do we decide worth? What is the power of the state for? When it comes down to it, where do you stand?

One of the many scenes which made me cry featured unarmed men on one council estate running at soldiers kitted out with batons, guns and riot gear, to try and buy their children time to run away. And one police officer, watching in horror, taking off his uniform to fight with the men he knew, rather than stay safe with the state.

Fantastical? Not so much. Can we really say, in Aotearoa today, that all of our children matter the same to the state?

The most obvious parallel is New Zealand armed police rolling into Tuhoe, treating the children of Ruatoki with absolute disdain. Police boarding schools buses, terrifying kids, detaining them illegally. It’s hard to imagine similar actions being signed off for buses headed to private schools in predominantly Pakeha areas.

But there are other parallels too, where the state might not be clad in riot gear. About 270,000 New Zealand children live in poverty, according to the Children’s Commissioner. These levels go up and down, depending on the state’s actions:

That’s

a lot of our children, living in poverty, in families where their

caregivers earn too little or the state allowances for looking after

children are insufficient.

When the state rolls up to reduce real

access to state allowances for those parenting, or introduce new

measures to allow employers to pay less than a living wage for parents,

or sells off state assets meaning essential services like power cost

more, what we are really doing is treating some children as less

important than other children.

It’s got a prettier face than Torchwood.

But the psychological process is the same, make no mistake. Distance.

Othering. Outright denial. Killing off empathy.

In Torchwood, the British government start

using “units” to describe the children they are sending to the aliens as

living happy pills. At Ruatoki, we talked about “terrorists” to

justify that school bus being boarded. And the language and images we

use to describe the poor? Subjective cartoon, anyone?

The motto of Torchwood Season One is: “The

twenty-first century is when everything changes. And you’ve got to be

ready.” Prescient? Or cheesy beyond compare, allowing those of us that

way inclined another chance to gasp admiringly at John Barrowman? Not

for the first time, I’m going to choose both.