Star Wars was my first movie, a metaphor for tolerance if not

celebration of difference if ever there was one. I’ve explored ideas

about social structures through science fiction ever since.

So when Torchwood began it was a no-brainer I’d be watching.

Aliens.

Gadgetry. Explicit and regular examination of gender and power.

Probably the hottest sex scenes, with all manner of couplings, I’ve seen

on a mainstream television show, because desire is explicit by everyone

participating. Set in Wales, so able to gently critique England as the

centre of the universe, and using that as a plot mechanism, repeatedly,

to explore issues of class. Every single main character exploring

attraction at one point or another to the same and different genders.

Aliens.

Gadgetry. Explicit and regular examination of gender and power.

Probably the hottest sex scenes, with all manner of couplings, I’ve seen

on a mainstream television show, because desire is explicit by everyone

participating. Set in Wales, so able to gently critique England as the

centre of the universe, and using that as a plot mechanism, repeatedly,

to explore issues of class. Every single main character exploring

attraction at one point or another to the same and different genders.

Season 3 is remarkable. Brutally stripped back plot spoiler: Aliens want to take 10% of Earth’s children as recreational drugs. They will release fatal viruses if Earth’s leaders don’t agree. They can do this; they have the technology.

What makes it remarkable is for the first time, Torchwood turns their beam on the machinations of the state responding to the crisis, in particular, the British government. A kinda sci-fi imagining of how western governments might react to such a dilemma.

We don’t come out well. The UK government had authorised, in 1965, a gift of 12 children to the same aliens, from a children’s home because “no one will miss them.”

The theme is extended to present day. First British ministers offer asylum seeking children in detention centres. When this isn’t enough for the aliens, the British state decides they cannot risk the children who will work in our hospitals and our schools, run our country. But the Deputy Prime Minister says some children matter less:

The British Ministers don’t like what they are doing. There is no joy. But there is the ability to decide that some people are worth less than others. That some people matter less. And therefore, the ability to sanction the unspeakable.

This series was almost unwatchable. As with all good sci-fi, the issues it was exploring were only human. How do we decide worth? What is the power of the state for? When it comes down to it, where do you stand?

One of the many scenes which made me cry featured unarmed men on one council estate running at soldiers kitted out with batons, guns and riot gear, to try and buy their children time to run away. And one police officer, watching in horror, taking off his uniform to fight with the men he knew, rather than stay safe with the state.

Fantastical? Not so much. Can we really say, in Aotearoa today, that all of our children matter the same to the state?

The most obvious parallel is New Zealand armed police rolling into Tuhoe, treating the children of Ruatoki with absolute disdain. Police boarding schools buses, terrifying kids, detaining them illegally. It’s hard to imagine similar actions being signed off for buses headed to private schools in predominantly Pakeha areas.

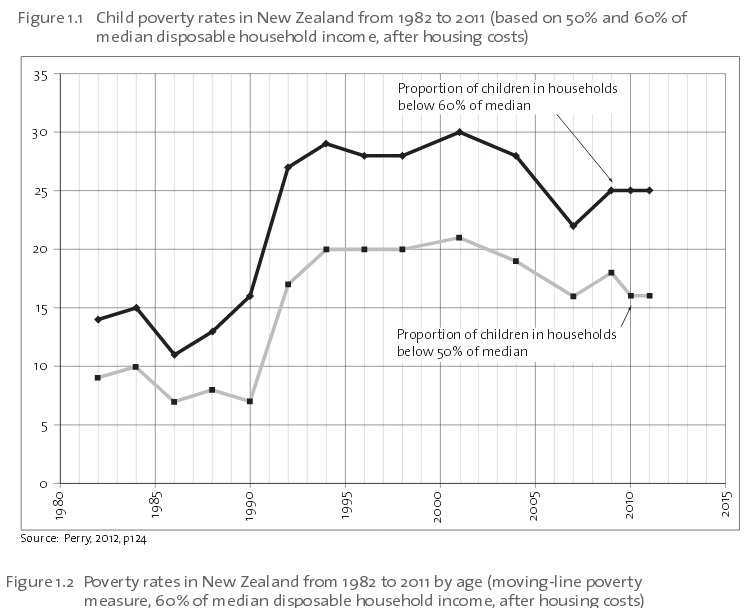

But there are other parallels too, where the state might not be clad in riot gear. About 270,000 New Zealand children live in poverty, according to the Children’s Commissioner. These levels go up and down, depending on the state’s actions:

So when Torchwood began it was a no-brainer I’d be watching.

Aliens.

Gadgetry. Explicit and regular examination of gender and power.

Probably the hottest sex scenes, with all manner of couplings, I’ve seen

on a mainstream television show, because desire is explicit by everyone

participating. Set in Wales, so able to gently critique England as the

centre of the universe, and using that as a plot mechanism, repeatedly,

to explore issues of class. Every single main character exploring

attraction at one point or another to the same and different genders.

Aliens.

Gadgetry. Explicit and regular examination of gender and power.

Probably the hottest sex scenes, with all manner of couplings, I’ve seen

on a mainstream television show, because desire is explicit by everyone

participating. Set in Wales, so able to gently critique England as the

centre of the universe, and using that as a plot mechanism, repeatedly,

to explore issues of class. Every single main character exploring

attraction at one point or another to the same and different genders.Season 3 is remarkable. Brutally stripped back plot spoiler: Aliens want to take 10% of Earth’s children as recreational drugs. They will release fatal viruses if Earth’s leaders don’t agree. They can do this; they have the technology.

What makes it remarkable is for the first time, Torchwood turns their beam on the machinations of the state responding to the crisis, in particular, the British government. A kinda sci-fi imagining of how western governments might react to such a dilemma.

We don’t come out well. The UK government had authorised, in 1965, a gift of 12 children to the same aliens, from a children’s home because “no one will miss them.”

The theme is extended to present day. First British ministers offer asylum seeking children in detention centres. When this isn’t enough for the aliens, the British state decides they cannot risk the children who will work in our hospitals and our schools, run our country. But the Deputy Prime Minister says some children matter less:

“If we can’t identify the lowest achieving 10% of this country’s children, then what are the school league tables for?”So the army rounds up children at school. Many, many parents keep their children home. The army rolls into working class areas, into council estates, and pulls children away from screaming parents.

The British Ministers don’t like what they are doing. There is no joy. But there is the ability to decide that some people are worth less than others. That some people matter less. And therefore, the ability to sanction the unspeakable.

This series was almost unwatchable. As with all good sci-fi, the issues it was exploring were only human. How do we decide worth? What is the power of the state for? When it comes down to it, where do you stand?

One of the many scenes which made me cry featured unarmed men on one council estate running at soldiers kitted out with batons, guns and riot gear, to try and buy their children time to run away. And one police officer, watching in horror, taking off his uniform to fight with the men he knew, rather than stay safe with the state.

Fantastical? Not so much. Can we really say, in Aotearoa today, that all of our children matter the same to the state?

The most obvious parallel is New Zealand armed police rolling into Tuhoe, treating the children of Ruatoki with absolute disdain. Police boarding schools buses, terrifying kids, detaining them illegally. It’s hard to imagine similar actions being signed off for buses headed to private schools in predominantly Pakeha areas.

But there are other parallels too, where the state might not be clad in riot gear. About 270,000 New Zealand children live in poverty, according to the Children’s Commissioner. These levels go up and down, depending on the state’s actions:

That’s

a lot of our children, living in poverty, in families where their

caregivers earn too little or the state allowances for looking after

children are insufficient.

When the state rolls up to reduce real

access to state allowances for those parenting, or introduce new

measures to allow employers to pay less than a living wage for parents,

or sells off state assets meaning essential services like power cost

more, what we are really doing is treating some children as less

important than other children.

It’s got a prettier face than Torchwood.

But the psychological process is the same, make no mistake. Distance.

Othering. Outright denial. Killing off empathy.

In Torchwood, the British government start

using “units” to describe the children they are sending to the aliens as

living happy pills. At Ruatoki, we talked about “terrorists” to

justify that school bus being boarded. And the language and images we

use to describe the poor? Subjective cartoon, anyone?

The motto of Torchwood Season One is: “The

twenty-first century is when everything changes. And you’ve got to be

ready.” Prescient? Or cheesy beyond compare, allowing those of us that

way inclined another chance to gasp admiringly at John Barrowman? Not

for the first time, I’m going to choose both.

18 comments:

Did you watch Season Four?

Forgive me if I have read this road, but didnt it get disprove that the police boarded school buses in Tuhoe?

Again I could be wrong.

I am a fan of Torchwood but it does have its problematic elements. Owen dropping essentially date rape drugs in women's drinks in season one(and it being presented as funny) anyone?

Edit: not in their drinks, I think it was a spray.

The welfare reforms courtesy of the Ministry of Social Development send a pretty clear message about the value of some children to our state.

3:16 - as to private school folk playing Rambo in their backyards, you'll be interested to know that the majority of gun owners in our country are middle class pakeha men... who use their weapons to get close to nature. Then kill it. Rambo enough for you?

Brett - the investigation was unable to substantiate the boarding of the bus, which is not the same as disproving it... but regardless, the raids terrorised children amongst others.

Wow LJ, I feel grumpy just thinking about the premise of Touchwood as you describe it. Probably because I'd really like to believe we live in a society that wouldn't let that happen, and yet we do live in a society that lets kids die - we might not hand them over to aliens, but we happily buy commodities that are cheap by their labour, or cheap by trade deals that let them starve.

Hi all, sorry for delayed responses. Hugh - just starting now, no spoilers please :-)

3:16 - your comment is deleted - containing racist, classist and misogynist slurs in it is just too much for me today I'm afraid. If you want to comment again, you'll have to be more thoughtful and less offensive.

Brett - you are right the IPCA report said the school bus boarding did not effect children. But my understanding is this is still disputed. If that's not right, apologies. If it is, I'm afraid I know who I believe on this occasion.

Danielle - I'm not sure I agree that Owen date-raping is problematic in Torchwood, precisely because in my opinion it's portrayed as problematic, and in the next episode or so, Owen "feels" the memory of a woman who was raped and murdered. The date-rape storyline does make Owen a hugely problematic character though, to me at least.

Rebecca - yep, agreed :-)

@LJ: No spoilers, I would be interested in your thoughts if you ever feel like sharing them here, though.

LudditeJourno:

Im probably wrong, it was just one thing on the internet that I read.

"...you'll have to be more thoughtful and less offensive."

I didn't mean to be offensive but you take what you want. Its your blog so you can make the rules but that's just PC for saying I have to say what you want to hear.

3:16

"The twenty-first century is when everything changes. And you’ve got to be ready.” "

It may've started 'cheesy', but it ended up more prescient than anything else on TV...

Our household was captivated by TORCHWOOD. It was so different. Gritty. And main characters had things happen to them after we got to love them. (No spoilers!)

Andyes, the 21st Century is where everything changes... The Arab Spring, Occupation Movements, Turkey, Brazil...

We have seen the enemy - and it is not alien, but a part of us.

By the way, qwhen I heard one of the Ministers on Torchwood: Children of Earth with this line,

“If we can’t identify the lowest achieving 10% of this country’s children, then what are the school league tables for?”

- that's when the political metaphor became apparent.

I was wondering if/when anyone else would pick up on it... ;-)

That one single statement must've gotten a fair number of viewers thinking. Imagine - slipping in a very brief, one-line subversive comment like that, and thrusting it upon Middle Class Brits watching it! I betcha the UK government wasn't pleased if they heard it...

Hugh - thanks, will see if I can justify another post on "sci-fi I love" :-)

Frank - sci-fi subversion, the best kind :-) I think the show does that around gender repeatedly too.

"I think the show does that around gender repeatedly too."

Oh yes, QoT, which is one of the reasons our household watched it religiously (we have the DVD series as well - but in small amounts as it can be depressing sometimes). Never mind the otherworldly creatures - the myriad depictions of human sexuality was far more "alien". And bloody entertaining to watch!

Ah, those Brits, they do 'Kink' exquisitely! (Mind you, if you remember Emma Peel in The Avengers... More leather and style than a church service at a knackers yard!)

It's amazing what those British private schools churned out...

:-D

However, there was one slight problem I had with it...namely the falling piano that crushed Ianto Jones in the penultimate episode.

Why is it that lesbian/gay couples never get to live happily ever after in prime time television? First Willow and Tara in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and then that?

Okay, there is some debate about dramatic neccessity within Torchwood fandom, but I wonder how things might have gone if it had been Gwen?

Imagine..."You bastards! She was pregnant!" "Yet another strong female character killed off..."

Added to which, Miracle Day was bungled because Russell Davies didn't deal adequately with Jack's loss of Ianto. Unlike Joss Whedon and Buffy season seven, it has to be said.

Craig Y

@Craig: Well, they killed Tosh and nobody seemed to care, so I'm not sure your 'what if it had been Gwen' thing is accurate.

@ Hugh - We CARED!!! I cried, dammit! (In a MANLY way, of course!)

;-D

By the way, for those who like the music, this is a medley on Youtube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yw3mmoykdjw&list=PL38316986FCDB919E

Post a Comment